How to shield neutrons

Dr. Michael Hua, Director of Radiation Safety and Nuclear Science

The building that houses Polaris has two main areas—the outer vault and the inner vault. These areas are separated by thick slabs of borated concrete and borated polyethylene that make up Polaris’s shielding. The outer vault contains the capacitor bank that powers the fusion machine, and the inner vault houses the mechanical structure of Polaris in which fusion occurs.

Byproducts of fusion include both clean, abundant energy and neutron radiation. The walls, ceiling, and foundation enclose the inner vault and exist to shield these neutrons, which can cause material in and around the machine to become activated, degrade our equipment, and, most importantly, pose a risk of radiation exposure to people. Shielding is one of the main measures we put in place to reduce those risks.

As we work toward building commercial fusion power plants, it is important to appreciate the risks associated with neutrons, recognize the role shielding plays in protecting against them, and incorporate appropriate shielding into our designs.

Shielding

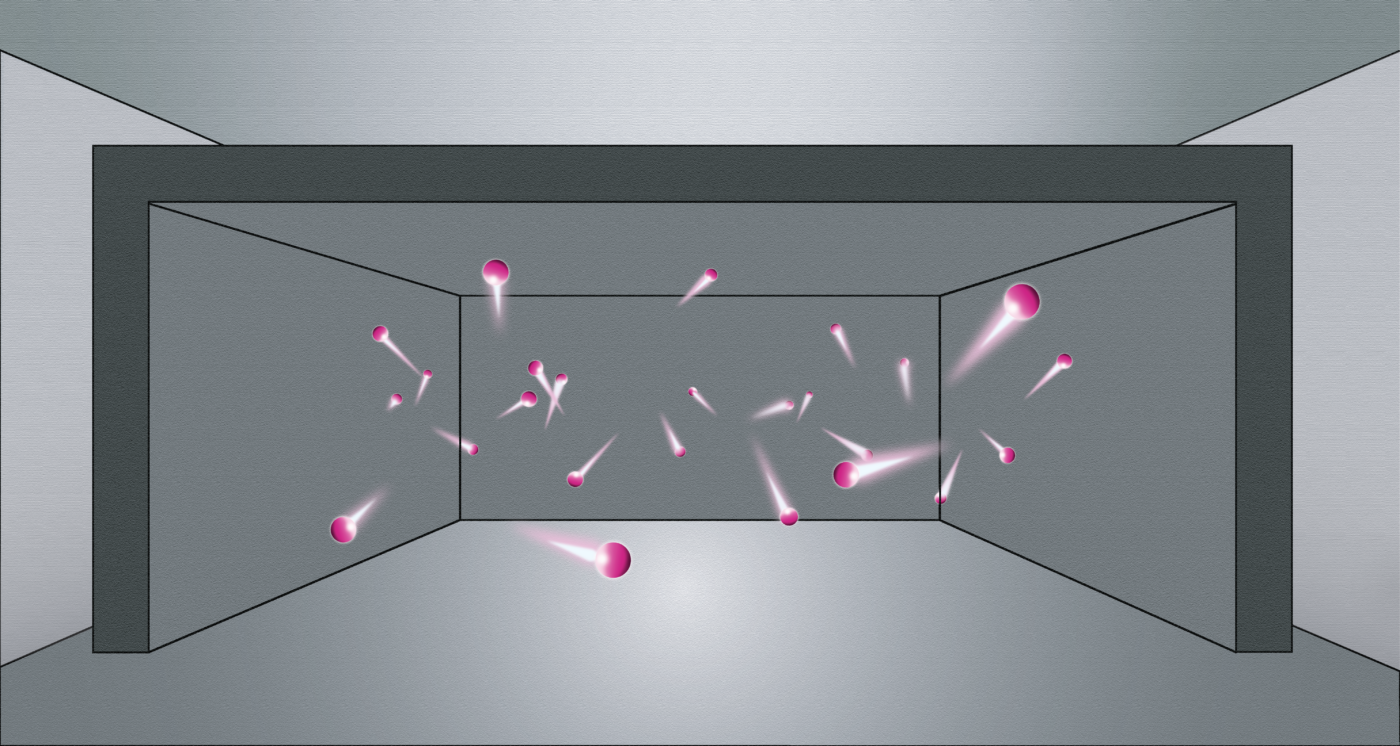

An analogy for shielding is to think of neutrons as soccer balls and the atoms in the shielding like trees in a forest. If you kick a soccer ball at a shallow row of trees, sometimes the ball will slow down and get stopped, and other times the soccer ball will make it through the trees and continue on. One way to reduce the number of soccer balls making it through the forest is to make it deeper. Similarly, one way to make neutron shielding more effective is to make the shielding thicker.

There are other ways for the forest to be more effective at stopping soccer balls. For example, the individual trees could be wider. Analogously, denser shielding can be more effective at stopping neutrons. Each individual tree can also be more effective at slowing down and stopping the soccer balls depending on the type of tree. A supple tree can bend and absorb most of the ball’s energy, whereas the ball can bounce off a firmer tree without losing much speed. Analogously, the shield’s efficiency can be increased by carefully selecting the material.

The shielding around Polaris utilizes borated high-density polyethylene on the inside and borated concrete on the outside. Polyethylene and concrete contain elements that are effective at slowing down neutrons; for example, polyethylene has a high hydrogen content and hydrogen can absorb almost all the neutron energy in a single collision. The boron additive is particularly adept at absorbing and removing slow neutrons. The process of slowing neutrons and absorbing them creates photon radiation. Concrete is effective at shielding these photons. The Polaris shielding was designed using simulation codes and guidance published by the National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements. As Polaris ramps up in power and neutron yield, monitors are used to ensure that our calculations are accurate and that radiation levels are as low as reasonably achievable.

ALARA

The guiding principle of radiation safety is to keep exposures to ionizing radiation like neutrons as low as reasonably achievable, or ALARA. This principle helps us determine how much shielding is required, and we also have clear guidelines provided by regulatory bodies like the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the Washington Department of Health (DOH). The DOH has been a strong partner as we have worked together on shields for several neutron-emitting machines, and they have been able to observe the Polaris shield in various stages of construction.

The main tenets of ALARA are using shielding, minimizing the time of exposure, and maximizing the distance from the radiation source. Hence, while shielding is a major part of our ALARA strategy, we also utilize access controls to limit time and ensure an adequate boundary around Polaris during operation—when the majority of the radiation is created—and while short-lived activated materials decay after operation.

From design to operations

Designing appropriate shielding requires consideration of the neutrons, utilization of the principles of ALARA, understanding the best materials to use, and open communication with regulators. We use standard neutronics software to simulate neutron and photon radiation levels inside the vault, outside the vault, and beyond the building. The finished result is a room atop a 3-foot-thick borated concrete pad with 5-foot-thick walls. Half of that thickness is borated HDPE, and the other half is borated concrete. Like the walls, the ceiling is layered with 18 inches of borated HDPE followed by 10 inches of borated concrete. The design process made conservative assumptions, and Polaris itself with all the other material around the machine will also contribute to shielding neutrons and photons.

As we ramp up Polaris test campaigns, we plan to go in stepwise fashion, all the while tracking the vault’s performance with radiation monitors at multiple locations. We will use those data to refine our simulations and adjust our safety systems if and where necessary.

When I see all the work we are doing, I know we are drawing closer each day to generating abundant, clean, carbon-free electricity with fusion. Doing so with clear eyes about the risks of radiation and care in how we mitigate those risks, we will also build the safest power plants in the world.